What are Victorian Trade Cards?

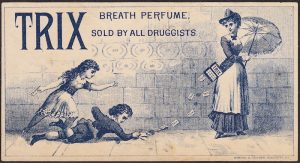

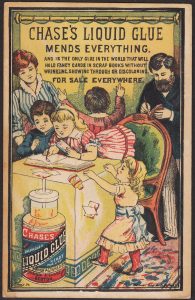

Victorian trade cards are illustrated business advertising cards from the 19th Century.

Typically printed in multiple colors, these cards were freely distributed to promote goods and services

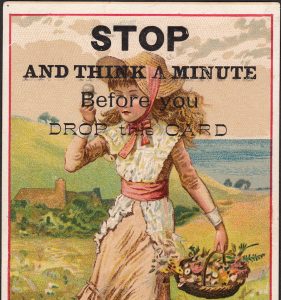

through images and messages designed to be so informative, so clever, or so attractive that

consumers would have a hard time throwing the ad away.

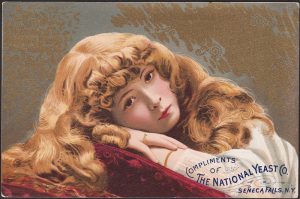

The quality of Victorian trade card illustrations can range from crude black and white comic sketches

to the breathtakingly beautiful life-like chromolithographs printed using 12 or more colors of ink.

Generally speaking, Victorian trade cards are approximately 3 x 5 inches, and most date between

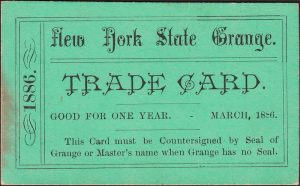

1876 and 1901. Cards from that period with only printed text and no illustrations are usually

considered “Business Cards,” or handbills if printed on thin paper and larger than a postcard.

Collectors often use the term “trade card” loosely, allowing the genre to include advertising

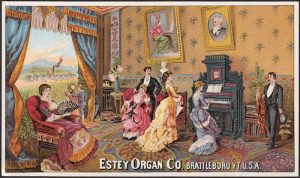

items not strictly “cards” in the usual sense. For example, while MOST Victorian trade cards are similar

to undersized postcards in size and shape, some trade cards can be as tiny as 1 x 2 inches, or as large as

5 x 9 inches. (Larger cards were more often used as “Display Cards” or “Counter Cards,” so they fall into the

category of cardboard dealer signs, as opposed to the mass-produced free trade cards for consumers.)

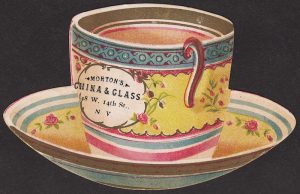

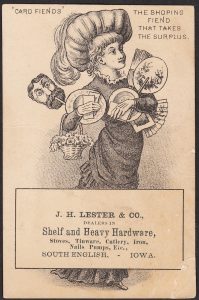

Additionally, Victorian novelty trade cards can be found in die-cut shapes, as well as in folding formats.

Sometimes they are even composed of wood veneer, celluloid, aluminum, or some other novelty material.

The Rise of 19th Century

Advertising Cards

Experts and collectors hold various opinions about what should be considered the oldest trade cards.

The term “trade” has to some extent fallen out of use, although one still occasionally hears references to

something like the “tourist trade” or a person learning the plumbing “trade.”

A century and more ago, the term was very common, and folks regularly heard and read about what was

happening in the shoe trade or the saloon trade, or what the tradesmen were doing about the unions.

Anyone conducting trade in clothing or groceries, or any craftsman in a trade like watchmaking, might

offer a “trade” card to a potential client to help promote their business or services.

It could be argued that the earliest trade and tradesmen cards were printed in Europe in the 1600’s.

Some of these cards included illustrations, but many did not.

The earliest known engraved American card of this type was produced around 1727 for a bookstore owned

by John Hancock’s uncle. Paul Revere was also known to print such cards during the time of the

American Revolution, and many of his designs were actually beautifully artistic.

Victorian trade cards, on the other hand, basically date to the late 1800’s, during the years of Queen

Victoria’s rule. In truth, the term “Victorian trade card” is a recent invention of modern collectors, authors,

dealers, and auction houses, including ebay. But it is a useful term that easily distinguishes these cards

from the earlier tradesmen cards and the blander “business” cards which lack illustrations.

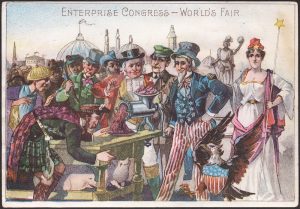

The “Golden Years” for American advertising trade cards began with their explosion in popularity as

free exhibit souvenirs from vendors at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

In 1876, the American Industrial Revolution was hitting full steam. Innovators and manufactures were

developing new products, and they were eager to showcase their goods and explain

the benefits of their brands in the most spectacular and memorable ways possible.

Full-color Victorian trade cards fit the bill perfectly.

In an age dominated by stark black and white photography and one-ink letter presses, the

rainbows of colors and extravagances in chromolithographed images made Victorian trade cards an instant hit.

Most of the early cards were produced by well-established lithographers in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York,

but as the popularity of Victorian trade cards skyrocketed, other printers began setting up color presses

and producing them in virtually every major city in America.

By the time of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and Columbian Exposition, a business could hardly be

considered respectable if it was not issuing cards worthy of a collector’s album.

Major lithographers like Ottmann of New York landed the biggest printing contracts with national firms

like Hires Root Beer and the Singer Sewing Machine Company, who placed orders for hundreds of thousands

of cards at at time.

But there was plenty of business for everyone, large or small.

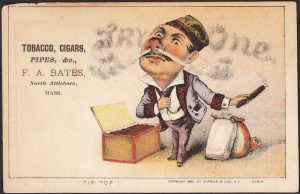

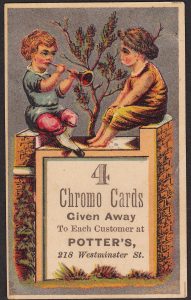

In remote villages, small-time entrepreneurs seized the opportunities by customizing cards

to the needs of even a handful of stores on Main Street.

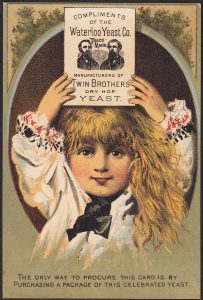

These go-getters would purchase an inexpensive box of assorted “stock cards” from the big cities.

Stock cards arrived in bulk with blank areas for imprinting local business names and addresses.

These cards could be imprinted one-at-a-time using inexpensive card presses which were sold mail order

for just such purposes.

An even less expensive option was to apply a name and address by means of a rubber stamp.

By the 1880’s, collecting Victorian trade cards had become a national craze.

Articles were written about the proper way to trim the margins off advertising cards so the distraction

of white borders would be eliminated when a card was pasted into a scrapbook.

Discussions were held on the merits of mounting cards with flour pastes rather than with leather glues.

Etiquette essays were written to instruct refined young women how to cluster their cards in themes,

as well as how to select certain types of albums to reflect the highest possible level of sophistication.

Children competed with neighbors to see who could fill the most parlor albums the fastest,

but parents got in on the fad as well.

Mothers would help the wee ones with their collecting, and in many cases, the scrapbook became

as much the mother’s project as anyone’s.

Men began seriously collecting cards in the late 1880’s when tobacco companies started issuing

sports cards, joke cards, and actress cards… with the interests of men in mind.

(Tobacco insert cards evolved into a genre of their own. More on that in a future article.)

How Victorian Trade Cards

were distributed:

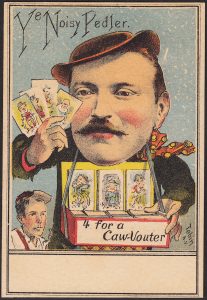

Victorian trade cards were often placed in stacks on store counters, free for the taking.

Other times, they were passed out by sales representative and noisy sidewalk “drummers.”

They could even be found packaged as “prizes” inside coffee tins or boxed products.

To exploit increasing demand, book stores started buying batches of cards to sell to collectors.

Collectors began writing to companies for free samples, or even sending money directly to printers

to purchase large assortments of cards before (or sometimes after) the ads were applied.

For those who have been collecting a long time, it is not uncommon to encounter multiple versions

of the same basic card: sometimes with wildly different imprints, and other times no printing at all.

Additional card variations occur when the same basic design is printed by different lithographers,

or when a printer remakes the plates or subsequently changes details at a client’s request.

By the mid-1880’s, Victorian trade cards were being distributed and collected from coast to coast,

from affluent urban centers to rural farm villages and remote mountain mining camps.

Today, many local historians and genaologists cherish these cards for the information they provide.

The Fall of

Victorian Trade Cards

The prestige of trade cards plummeted after the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition World’s Fair of 1901.

By the arrival of the 1900’s, colorful magazine ads were on the rise, and the new fad of collecting postcards

was taking the nation by storm.

For the “modern” young people of the new century, assembling and organizing hand-addressed postal cards

was all the rage. Filing and shuffling their exotic treasures in the slotted black pages of post card albums

made gluing Victorian trade cards seem messy, and more like something “old-fashioned” only their mothers would do.

Queen Victoria ruled the UK from 1837 until she died of old age in 1901.

It seems fitting that as the Victorian era passed away and made room for the innovations of the 20th century,

so, too, did Victorian trade cards fade away and yield their preeminence to modern advertising

and the new cards that became in many ways the equivalent of Twitter and Selfies today.

But more on the transition from trade cards to postcards at another time.

Again, as always, all the BEST to you… and Good Collecting! — Dave Cheadle