Bigotry and Ethnic Stereotyping in 19th Century Advertising Card Images

Racist attitudes flourished in the 1880’s, and they were backed by some of the “best” so-called science of the day.

Fueled by Darwin’s theories and naive “new insights” from studies in fields like anthropology and phrenology, some of the most educated Victorian-era elites were among the period’s biggest bigots, and “scientific racism” flourished.

Of course, one didn’t have to be a 19th Century intellectual to be a racist.

The “sport” of racism was open to all.

Chinese and African-American Blacks

Negative stereotypes of numerous people groups appear in hundreds of Victorian Advertising Trade Card images. In future articles and blogs, we’ll explore more examples of racial profiling in advertising, and the way many ad cards depict Japanese people, as well as Native American Indians, and immigrants of French, Jewish, Arab, and Spanish heritage.

But in this blog, I will launch into the subject of 19th Century racial profiling in advertising via a close look at one particularly representative –and reprehensible– example of ethnic stereotyping as found on a card issued for “Allen’s Jewell Five Cent Plug Tobacco.”

Racial Profiling in Advertising:

Allen’s Jewel Plug Tobacco

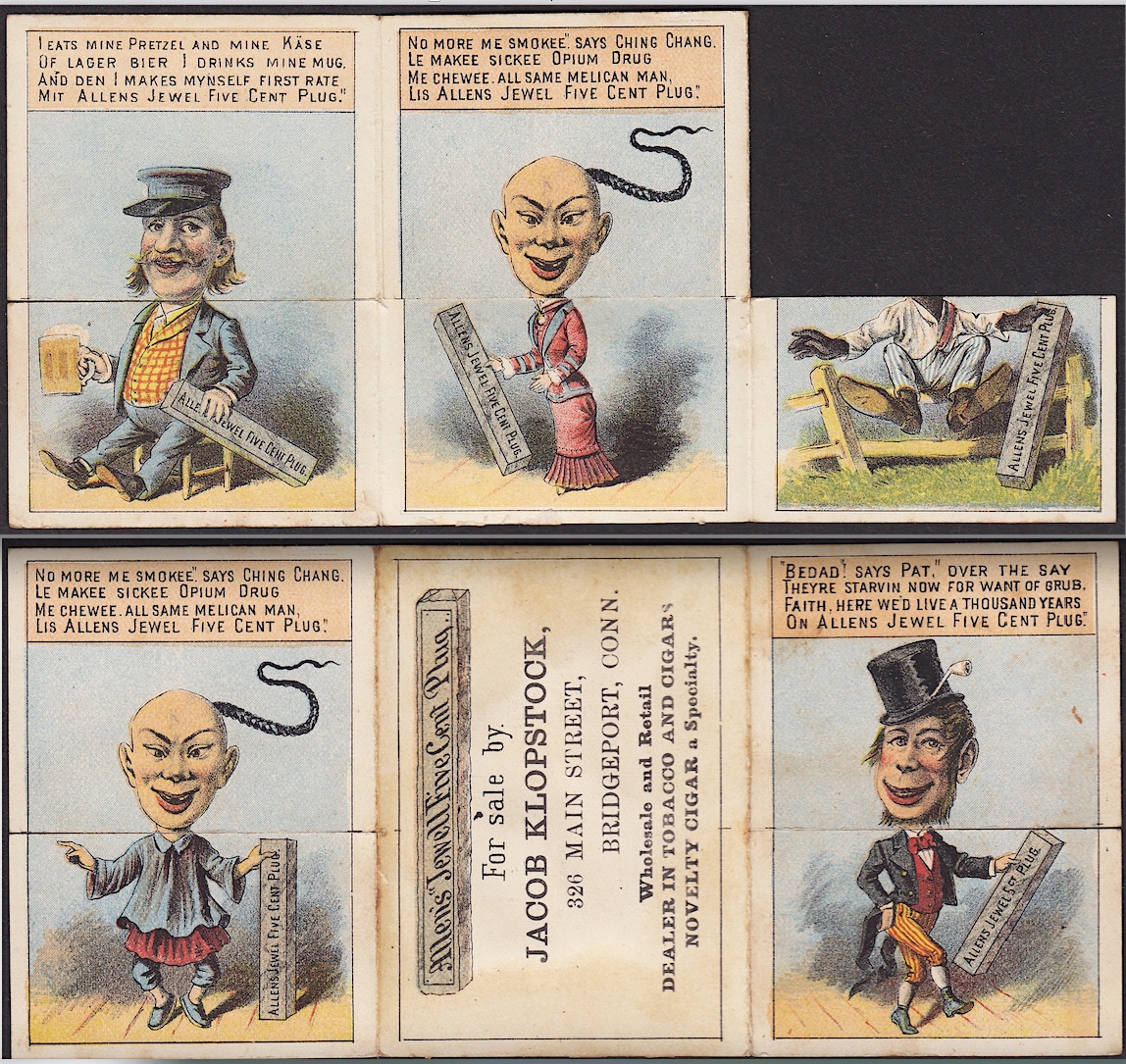

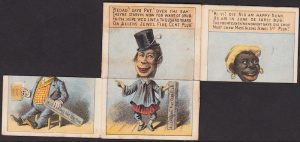

This “Allen’s Plug” 19th Century Tobacco Card is of the novelty type known as a “Metamorphic.”

Most metamorphic cards have one flap the folds either up or down (or left to right) in order to change the scene and tell an often humorous story of transformation — typically from a state of misery to a place of joy after finding the correct product to improve the character’s situation.

With this circa 1880’s card, we find four double-sided flaps designed to create multiple “mix and match” ethnic and gender absurdities. Poems, written in the supposed “dialect” of each group being ridiculed, accompany each head shot. Additionally, the stereotyped “flaws” of each group are elevated in the spirit of classic Victorian “humor.”

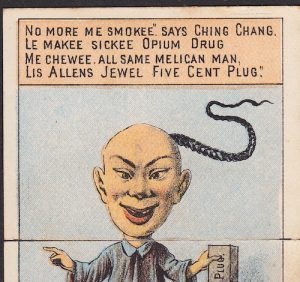

For “Ching Chang,” the laborer from China, Allen’s tobacco offers an upgrade from opium, as well as an opportunity for the man to become “all same melican man” — the same as an American man.

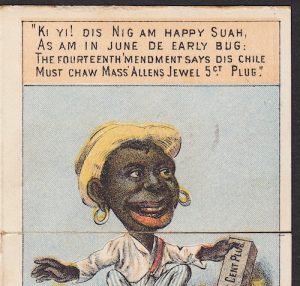

For the former slave from the South, “Dis Nig” is now happy, sir. Why? Because “Dis Chile” thinks the Fourteenth Amendment says he must chew “Master Allen’s” nickle plug tobacco. And he likes it!

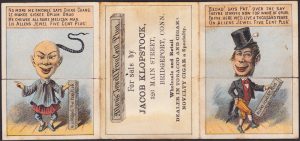

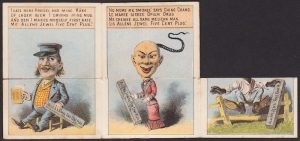

Irish Jig Dancing Nonsense

Heels up and clay pipe firmly tucked into his hat, the monkey-faced Irishman of this metamorphic tale grins and dances a jig; in his sly simian way, he declares the Irish famine to finally be over… thanks to affordable tobacco.

And then, if you manipulate the racist flap images a certain way, you can bring the nonsense of the Irish dancer and the aspirations of the Chinese laborer into a composite new monstrosity. Their merger becomes a bigot’s dream come true… a “comical” figure not to be taken seriously at all.

In the pseudo-scientific literature of the 1800’s, the “ape-like” Celt took a beating. For example, Charles Kingsley wrote that he was “haunted by the human chimpanzees” he saw in Ireland, and that “to see white chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black, one would not feel it so much. . . .” (see: L.P. Curtis, Anglo-Saxons and Celts: A Study of Anti-Irish Prejudice in Victorian England, 1968, 84).

The mean-spirited edge found in most of the cards that are guilty of racial profiling in advertising is usually directed at African-American Blacks and impoverished Chinese and Irish laborers.

The stereotypes are greatly softened in nearly all representations of German-Dutch immigrants.

The worst that can be said of these Beer-Drinking and Pretzel-Munching jolly good fellows is that by-and-large, they’re overweight.

Then again, in the 1800’s, a man’s thick waist was viewed as a proof of intelligence and industry, and both were admired traits guaranteed to produce the rewards prosperity… with endless good eating.

A “Tip of the Hat” to Gender Roles

The final panel of this card depicts a Victorian beauty, classically adorned in her corset and bustle, topped with an elaborate hat. Trim and radiant, the angelic blonde “Angeline” smiles: “Won’t George be pleased.”

This angel is a fine woman, indeed. For on this particular day’s shopping adventure, George’s petite little jewel from the Victorian parlor thought of her beloved hubby, and she returned from the market with something to present her man in addition to her ever-treasured smile:

a plug of Allen’s Jewel Five Cent Chew.

Because many trade cards were issued to advertised products marketed specifically to the female shoppers of the average Middle-class household, women were often honored — if not exalted — in 19th Century ads. Their beauty and poise, and their wisdom and grace, were often above reproach, if not approach.

In the case of this particular a male-centric advertisement, however, the woman is neither untouchable nor beyond manipulation.

With a quick folding or two of the flaps, the lovely and entitled Victorian Angeline succumbs to the imposition of a Chinese commoner, who is all too eager to weasel his way into the American man’s world!

In sum, this one card carries an amazing load of bias. As uncomfortable as an exploration of these ugly themes may feel to most of us today, a card like this is an historically important artifact. It opens a window and sheds light on dark days, times when even the images and language of advertising drifted into hateful places that were largely accepted by the dominant culture of the day.

=================================================================================

Check back for future blogs on Racial Profiling in Advertising, as well as many other fascinating Victorian Card topics and visual themes!

Meanwhile, Good Collecting! — Dave Cheadle